MONROVIA (AFP) – Hundreds of children have been killed by the Ebola epidemic ravaging west Africa, yet for the thousands spared, the grim struggle for survival has only just begun.

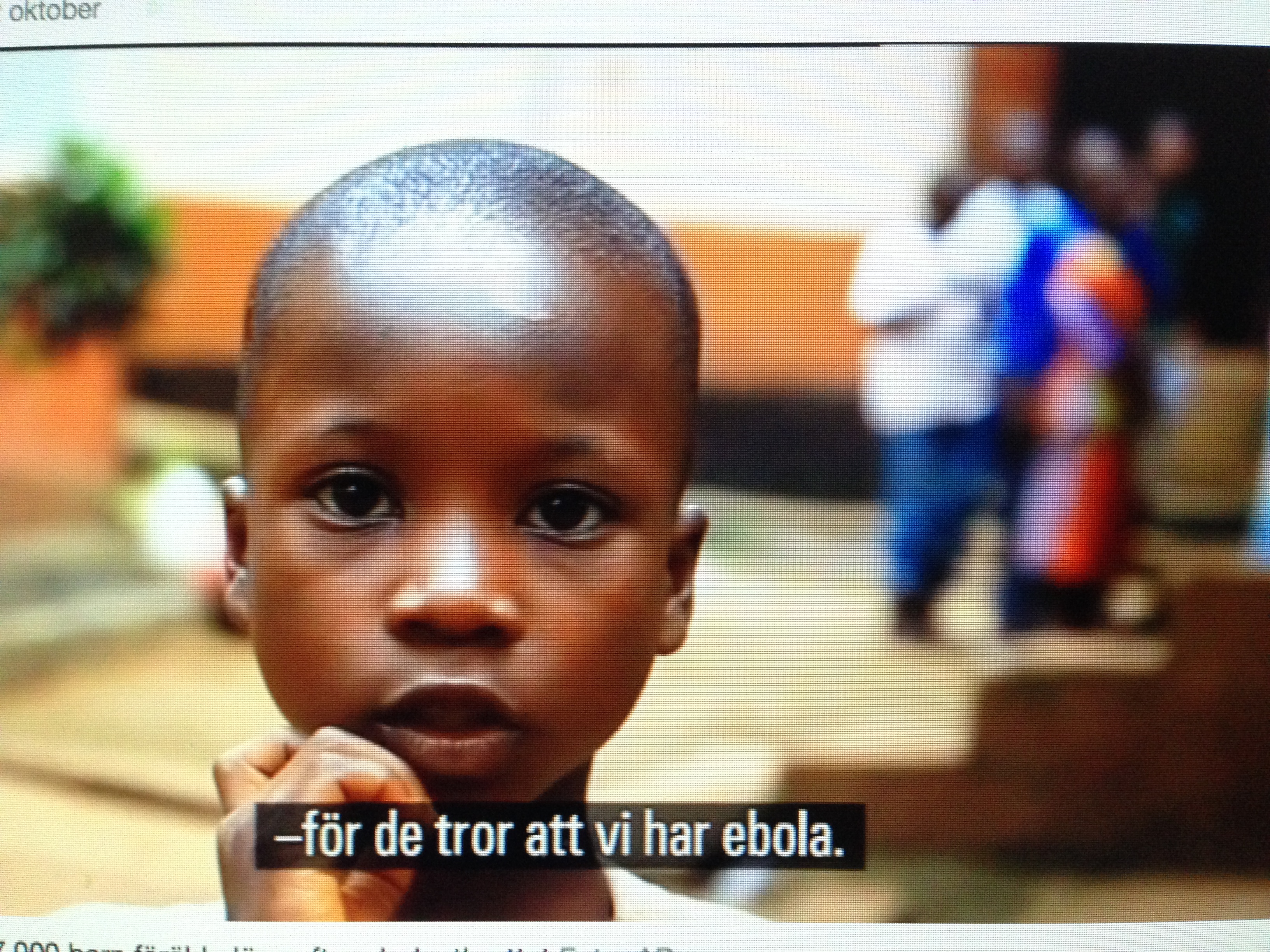

Children across Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea are finding themselves alone in the world, ostracised by communities terrified by the contagion and without family to look after them.

“It was different with the HIV epidemic,” says Unicef spokesman Sarah Crowe, referring to the system of extended family and friends taking on Aids orphans.

“It was a safety net. Now with the fear of Ebola, the system has broken down,” she says.

Ebola, which has killed around half of the 7,000 people it has infected in the world’s worst-ever outbreak of the virus, is spread through contact with infected bodily fluids.

One of the most shocking consequences of its deadly march through west Africa is the plight of children of the adult victims who wander the streets or clog up treatment centres, with nowhere to go.

“They continue to suffer from the impact of Ebola by loss of family members, stigma and rejection from community members and even relatives for fear of contracting the virus,” said Krista Armstrong of the British charity Save The Children.

The majority of people who are dying in the outbreak are aged between 25 and 45, according to Crowe.

But around 500 under 15s have also died, according to Unicef regional director Manuel Fontaine. Those who have lost at least one parent number in the thousands, the agency estimates.

Across the three hardest-hit countries are children who have survived infection but lost their parents or been abandoned by their families.

“The most difficult thing is a child whose family has been affected by the disease… while the child is negative. They are supposed to be isolated for 21 days but there are no facilities,” said Laurence Sailly, coordinator of an Ebola treatment centre run by Medecins Sans Frontieres in Monrovia.

One such case is five-year-old Harry, who turned up at the centre with his sick parents in late September.

His parents were sent immediately to the “red zone”, which only 40 per cent of patients leave alive, while Harry spent several days in the “green zone”.

Caregivers took turns during their breaks to keep him company, giving him crayons and paper to pass the time as his parents fought a losing battle nearby against the virus.

Finally, Unicef found a family of Ebola survivors to look after Harry, whose name has been changed to protect his identity.

This temporary solution may have to become permanent: Harry’s father died and his mother was in the final stages of the fever when AFP visited the centre on Sunday.

“We have created a ‘survivors network’, with which we try to look after the children,” says Unicef’s Crowe.

The agency, which is contributing to the training of 400 social workers and mental health professionals in Liberia, has announced a comprehensive plan to find carers for children in Sierra Leone.

Over the next six months, more than 2,500 survivors, who appear to be immune to recontamination, will be trained in Sierra Leone to care for children in quarantine, according to Unicef.

In Guinea, the agency is providing psychological support to 60,000 vulnerable children and their families in areas affected by Ebola.

Even in the grim category of children turned into orphans by Ebola, there are some who are less fortunate than others.

Some, for example, are “hidden” orphans – children of Ebola victims whose deaths were never officially declared, who are not even recognised as part of the crisis.

“Every day there are children at home without parents, and the community is afraid to help,” said Crowe.

The preferred solution is always to try to find the family, says Armstrong, but if this proves impossible, NGOs seek host families to whom they provide basic financial support.

Facilities providing temporary accommodation have also been set up for infant survivors or those requiring quarantine.

But there are not enough of these facilities in Liberia, Guinea or Sierra Leone which are among the poorest on the planet and are not receiving enough help from the international community.

Unicef says it has received just a quarter of the US$200 million (S$254 million) it deems necessary for its work on Ebola.

– See more at: http://www.straitstimes.com/the-big-story/ebola-virus-2014/story/thousands-ebola-orphans-facing-grim-fight-survival-africa-20141#sthash.SMssLOPK.dpuf